Word structure

TRS is a VSO language that consists mainly of monosyllabic and disyllabic words. Trisyllabic words are compounds and are not as common. Compound nouns may consist of a noun with another noun, verb or adjective. For example, in the text, [ʒukwaː5 t̪oː2 jaʔaː3] ‘plumed serpent’ is a compound consisting of ‘snake – feather – brush’. Hollenbach (2008:31) notes that over time, some compounds in TRC came to be pronounced as one word thus resulting in a new noun. The same is true for TRS. For example, in TRS [rat͡ʂũː53] ‘bread’ is derived from [t͡ʂaː3] ‘tortilla’ and [t͡ʂũː53] ‘oven’. Some blended words resulted in three-syllable nouns, for example, ruguachra‘a [ruɡwat͡ʂa2ʔa] ‘plank – board’, derived from [t͡ʂũː3] ‘tree, stick’ and [ɡat͡ʂa2ʔ] ‘wide’ or ruguchrïn [ruɡut͡ʂɯ̃ː3] ‘pine tree’ comes from [t͡ʂũː3] ‘tree’ + [ɡut͡siː3] ‘pale’, according to one consultant. Days of the week may also result in three-syllable compound nouns, for example, güigàn’anj [ɡwi3ɡã1ʔã3h] ‘Thursday’ consists of güi [ɡwiː3] ‘sun – day’ and gàn’anj [ɡã1ʔã3h] ‘four’ while güidungu [ɡwidũŋɡuː3] ‘Sunday’ is a blend of TRS and Spanish, consisting of güi [ɡwiː3] ‘sun – day’ and dungu -[dũŋɡuː3] from the Spanish domingo for ‘Sunday’. Complex lexemes are underlined in the text below.

TRS final syllables are accentually prominent and carry phonemically contrastive tone, except for the formation of the future and past tenses as discussed below. Final syllables end in a long vowel [Vː] or in a coda consonant /ʔ h/. Word final /n/ signals nasalization of the previous vowel as in the word ru’man [ruʔmãː3] ‘hole’ in the text below. Leftward spreading of nasalization is thwarted by an intervening laryngeal, either glottal stop /ʔ/ or /h/ except for cases in which the root is nasalized, for example, hian’anj an [j̃ã2ʔã2hã] ‘God’, nuguan’an [nuɡwãʔ2ã] ‘word’ or hian’àan [j̃ãʔãː13] ‘twins’. Final vowel nasalization may also occur in morphophonological forms and serves as a marker of 3SG short or fused forms in verbs, possessed nouns, predicate adjectives and prepositions, for example, unïï̀’ïn [u3nɯ31ʔɯ̃ː3] ‘he-she fights’ from unïì’ [u3nɯ31ʔ] ‘fight’; si-naton on [siː32 nat̪õː2õː3] ‘his-her banana’ from nato [nat̪oː2] ‘banana’; hìo on [j̃õː13õː3] ‘he/she is quick’ from hìo [joː13] ‘quick’, and ngàn an [ŋɡãː1ãː3] ‘with him/her’ from ngà [ŋɡaː1] ‘with’ (Edmondson et al. 2012; research in progress).

Chicahuaxtla Triqui nouns are not inflected for number or gender. When number is of importance, nouns may be preceded by a plural marker /ne3h/, which is also used to convert singular pronouns to their plural form. Nej [ne3h] is also used as a plural definite article as well. The following examples are found in the text:

| (1a) | ne3h | ʒi4ʔ | ||

| PL | elder | |||

| ‘our elders’ | ||||

| (1b) | ne3h | so4ʔ | ||

| PL | he | |||

| ‘they’ | ||||

| (1c) | ne3h | ɡwiː3 | ||

| PL | person | |||

| ‘people’ | ||||

| (1d) | ne3h | sat͡ʃi3hi | ||

| PL | ancestor | |||

| ‘ancestors’ |

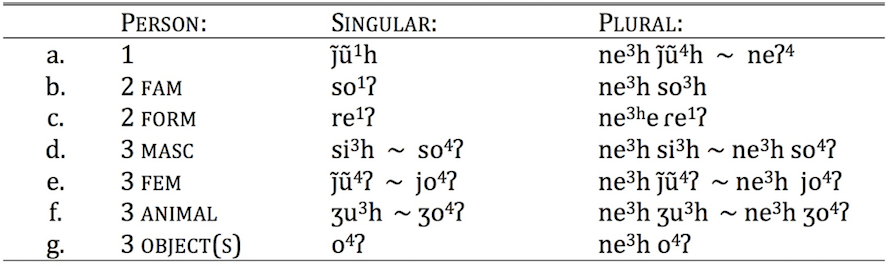

TRS has a rich set of free pronouns with approximately 30 different forms. Personal pronouns are invariable insofar as the same forms are used as subject, direct object, indirect object, the object of a preposition or the subject of a predicate adjective. Grammatical function is conveyed by means of word order or through the use of prepositions. Only the most commonly used pronouns are listed in Table 5 below.

TABLE 5: Free Pronouns in TRS

While all pronouns reflect person and number, others are conditioned by natural or biological gender of the referent, speaker gender (i.e., pronouns specifically used by men while others are used by women), social deixis (i.e., formal and familiar forms) and endophoric reference. For example, males use two alternate forms for 3SG:MASC: [si3h] and [so4ʔ]. The former is used the first time that one refers to the 3SG:MASC person while the latter is used for subsequent reference to the same male in discourse. In other cases, when a male is talking about two males, he will refer to the first man using /si3h/ and to the second using /so4ʔ/. The same rules apply to [j̃ũ4ʔ] and [jo4ʔ] ‘she – her’ and corresponding plural forms. In TRS, singular pronouns are changed to plural forms by adding a plural morpheme /ne3h/ (/ne3he/ for 2PL) before the singular pronominal form.

Another group of pronouns is used when referring to animals or inanimate objects (i.e., things). In (f), the pronoun /ʒu3h/ ‘he.animal’ is used when referring to an animal for the first time, while subsequent reference to the same animal takes the pronoun /ʒoʔ4/. In the text below, the speaker first refers to the Plumed Serpent by using an overt compound noun in line 4, [ʒukwaː5 t̪oː32 jaʔaː3] ‘plumed serpent’ while /ʒoʔ4/ ‘he.animal’ occurs throughout the remainder of the text.

The pronouns presented here and used in the text below reflect male speech. Longacre (1952:114) notes that women speakers use pronouns that are different from those used by men.

Glottally interrupted final syllables

Unlike the other Triqui languages, TRS has glottally interrupted vowels in final syllables in which a single vocalic gesture is interrupted by a laryngeal, either /ʔ/ or /h/ in nominal forms. First reported by Longacre in 1952, glottally interrupted syllables in TRS consist of one nucleus, either glottal stop /ʔ/ or /h/, in which phonemically contrastive tone is found throughout the entire vowel save for the perturbation in tone trajectory from glottal constriction in mid-syllable. This unique combination of words that contain mid-syllable interrupts, either /VʔTV/ or /VhTV/ and those that have vowel-glottal stop-vowel sequences, i.e., /VʔVT/, has significant consequences for the tone-laryngeal morphophonological system of TRS for it is precisely the combination of the laryngeal gesture, either glottal stop /ʔ/ or /h/, along with the tone of the glottally interrupted vowel that determines the correct morphophonological patterns that emerge. Syllables that are interrupted by a glottal stop /ʔ/ have a [Vʔ]-stem rime sequence and while those that are interrupted by /h/ have [Vh]-stem rime sequence. For example, the TRS word [t͡ʂa3ʔa] ‘song’ is a mid-syllable interrupt that has a /Vʔ/ final stem rime while the word [t͡ʂe3he] ‘road’ has /Vh/ final stem rime. Both of these examples follow a tone-laryngeal pattern for lexical items ending in tone /3/. Although glottally interrupted forms most commonly occur with tone /3/, other combinations, such as /Vʔ1V/, /Vʔ2V/ and /Vh1V/, /Vh2V/ are possible, for example, nuguan’an [nuɡwãʔ2ã] ‘word’ or hiàn’àn [j̃ãʔ1ã] ‘night’. Glottally interrupted syllables do not occur with high or extra high tones.

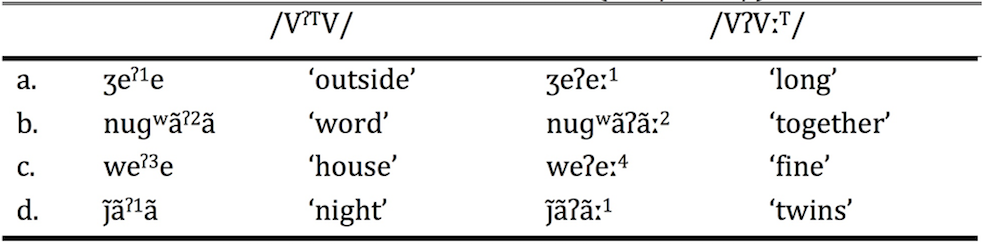

Longacre (1952:75 fn2.1) states that glottally interrupted syllables do not undergo final vowel lengthening as vowel-glottal stop-vowel sequences do. There is a word-final constraint in TRS that vowels in word-final contexts must be lengthened. This constraint can differentiate minimal pairs with glottally interrupted vowels that are interrupted by a glottal stop /ʔ/, e.g., [VʔTV], from “true” vowel-glottal stop-vowel structures [VʔVT] as in the following examples in Table 6 below:1

TABLE 6: Minimal Pairs Comparing Glottally Interrupted Vowels to Glottal Stops in Intervocalic Position

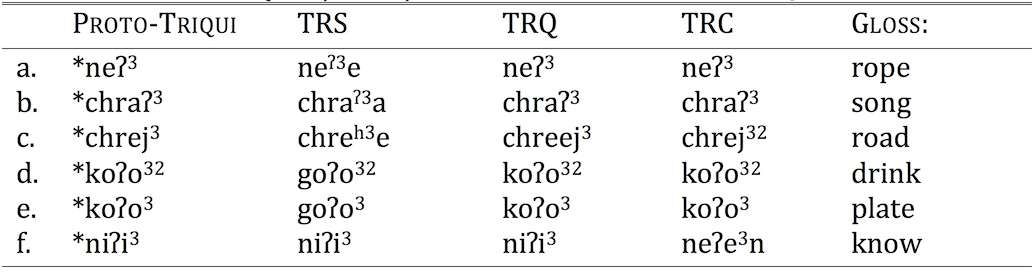

Glottally interrupted vowels (e.g., /VʔTV/) are not found in TRC or TRQ. Table 7 compares lexical items with glottally interrupted syllables and intervocalic glottal stops (e.g., /VʔVːT/) to cognates in TRQ and TRC. Words (a) – (c) have glottally interrupted vowels in TRS and correspond to monosyllabic cognates in TRC and TRQ. Items (d) through (f), however, are true vowel-glottal stop-vowel sequences in all three language in which phonemically contrastive tone is found on the last vowel.

TABLE 7: TRS Glottally Interrupted Vowels and Vowel-Glottal Stop-Vowel Sequences Compared to Cognates in TRQ and TRC

NOTE: Data for Itunyoso Triqui are from DiCanio (Personal Website Database) and those for TRC are from Hollenbach (2016). Proto-Triqui reconstructed forms are based on Matsukawa (2008).

There are a few examples of glottally interrupted vowels in the text below, for example, sachij i [sat͡ʃi3hi] ‘elders – ancestors’ or nuguan’an [nuɡwãʔ2ã] ‘word’ and kïj [kɯ3h] from kïj ï [kɯh3ɯ] ‘mountain’. The laryngeal features in glottally interrupted syllables are superscripted to show these words are one-syllable constructions, (e.g., /ʔ h/ ) while vowel-glottal stop-vowel structures are transcribed with the /ʔ/ written on the line.

Verbs, Tone, and Aspect.

Probably the most comprehensive attempt to uncover any underlying systematicity with TRS tone-laryngeal verb morphology, its conjugations and aspect morphology can be attributed to Good (1979) and is found in the appendix of his Chicahuaxtla Triqui-Spanish/Spanish-Triqui language dictionary, (available online at the Summer Institute of Linguistics website at: https://www.sil.org/resources/archives/10957). A significant finding with this and other related studies is that the TRS data collected today largely corroborate the TRS verb classification system and aspect morphology as outlined per Good (1979:105-107). Although the system appears to have diversified slightly over the years through the incorporation of new lexical items and Spanish and English borrowings, the overarching patterns as outlined by Good appear to have remained largely intact and relatively stable over the years with some exceptions. For example, Good (1979:22) documents the TRS verb ‘sell’ as [duʔwe4h], ending in a high register tone, however, based on current research, native speakers pronounce this form as [duʔwe2h] in tone /2/. It is difficult to speculate what may account for this discrepancy.

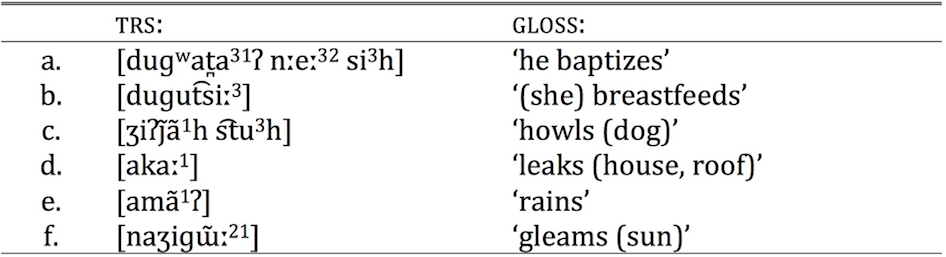

TRS verbs occur in three possible tenses: PRESENT, PAST and FUTURE.2 If the verb expresses actions that can be carried out by everyone, the form naturally given by the native speaker consultant is in the 1INCL form of the future tense. For example, [ɡa2ʔmi2ʔ] ‘we are going to speak’; [ɡa2t̪oː2ʔ] ‘we are going to sleep’, and [ɡu2nɯ4ʔ] ‘we are going to hear (him, her, it)’. Actions that are carried out by animals or inanimate objects, for example, howling or leaking, or those that are limited to specific individuals such as baptizing a person or breastfeeding a child are given in the 3SG form (Good 1979:105) of the present. Sample verbs of this type are illustrated in Table 8 below.

TABLE 8: Sample Actions Limited to Specific Individuals, Animals or Inanimate Objects in TRS

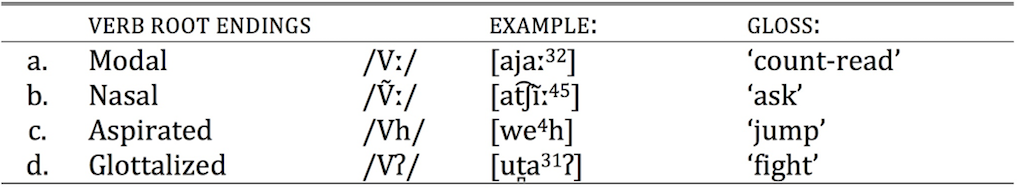

Verb roots in TRS may end in a modal, nasalized, aspirated or glottalized vowel, (e.g., /Vː/, /Ṽː/, /Vh/, /Vʔ/) as per the examples listed in Table 9 below:

TABLE 9: Sample Verb Roots in TRS

In the formation of the present tense, the verb root or stem is used before a free pronoun, for example, [at͡ʂaː35 ɾe1ʔ] ‘you sing’, [duʔwe2h ne3h si3h] ‘they sell’ or [unɯ31ʔ si3h] ‘he argues’. Verb roots may also be used before an overt noun as in the sample excerpts from the text below.

| (2a) | ɡananɯ4 | ne3h | ʒiʔ4 |

| ɡa–nãnɯ̃ː4 | ne3h | ʒiʔ4ʔ | |

| PST–tell | PL | elder | ‘our elders told us’ |

| (2b) | ɡanaʧi3 | nita3 | nːe32 |

| ɡa–nat͡ʃː3 | nit̪aː3 | nːeː32 | |

| PST–flow | fountain | water | |

| ‘water springs flowed’ | |||

| (2c) | ɡata3h | ne3h | sat͡ʃ3hi |

| ɡa–t̪a3h | ne3h | sat͡ʃ3hi | |

| PST–say | PL | ancestor | |

| ‘the ancestors said’ |

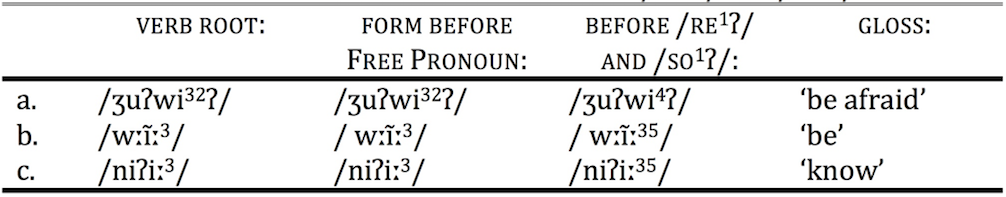

Although the tone of the root does not usually change before the majority of free pronouns, there are some verbs in which the tone or tone contour may change before the free pronouns /re1ʔ/ and /so1ʔ/ ‘you’ 2SG form and FAM, respectively. For example, /ʒuʔwi32ʔ/ ‘afraid’ is the root that is used before all other free pronouns but it raises to tone /4/ before /re1ʔ/ and /so1ʔ/ as in

/ʒuʔwi4ʔ re1ʔ/ ‘you are afraid’ (2SG form) and /ʒuʔwi4ʔ so1ʔ/ ‘you are afraid’ (2SG:FAM). Other examples of tone allomorphy before the pronouns /re1ʔ/ and /so1ʔ/ are included in Table 10 below.

TABLE 10: Examples of Tone Allomorphy before /re1ʔ/ and /so1ʔ/ in TRS

TRS has two separate systems for indicating the subject in the formation of 1SG and 1INCL forms. The first consists of using the root before a free pronoun while the second employs systematic changes in the tone of the root and at times, the addition of clitic pronouns for marking person and number, for example, the addition or deletion of /=h/ for 1SG or the addition of glottal stop /=ʔ/ for 1INCL. For example, native speakers of TRS may say [duʔwe2h j̃ũ1h] ‘I sell’ using the root before the free pronoun [j̃ũ1h] ‘I’ or a fused form [duʔweː43] ‘I sell’ without an accompanying free pronoun. Likewise, the verb root for 1INCL may be used before the pronoun /j̃ũ1ʔ/ ‘we’ as in /aʔmiː32 j̃ũ1ʔ/ ‘we speak’ or a fused equivalent form /aʔmi4=ʔ/ ‘we speak’, without a free pronoun.

Native speakers refer to forms that are used with a free pronoun as long forms while the lexical items that mark person and number by means of tonal changes, either changes in tone height or contour, and/or the addition or deletion of clitics are referred to as short forms. Native speakers of TRS tend to use 1SG and 1INCL long and short forms with roughly the same amount of frequency. The choice of form, long versus short, is not dependent upon the root of the verb.

Table 11 lists several examples of 1SG long and short forms in TRS. Person and number are marked by a variety of means in the formation of the 1SG short forms. For example, the root form may undergo changes in tone height as illustrated by (a) /aʔmiː32 j̃ũ1h/~ /aʔmiː43/ ‘I speak’. Other forms may undergo changes in tone height plus the addition of laryngeal /h/, as in (b) /ɡoʔoː32 j̃ũ1h/ ~ /ɡoʔo4=h/ ‘I drink’. Items (d) through (f) have changes in tone height and undergo /h/ deletion in the formation of the 1SG short form, as in (d) /duʔwe2h j̃ũ1h/ ~ /duʔweː43/ ‘I sell’; (e) /o4h j̃ũ1h/ ~ /oː43/ ‘I shell (corn)’ and (f) /rã4ʔã1h j̃ũ1h / ~ /rã4ʔãː43/ ‘I dance’ while (g) /ut̪a31ʔ j̃ũ1h/~/ut̪aː35/ ‘I fight’ changes in tone height and undergoes glottal stop /ʔ/ deletion. There is yet another small group of verbs that undergo final syllable reduplication and the addition of laryngeal /h/, as in (h) /sa1ʔ j̃ũ1h/ ~ /sa1ʔa1=h/ ‘I am good’.

TABLE 11: 1SG Long and Short Forms in TRS

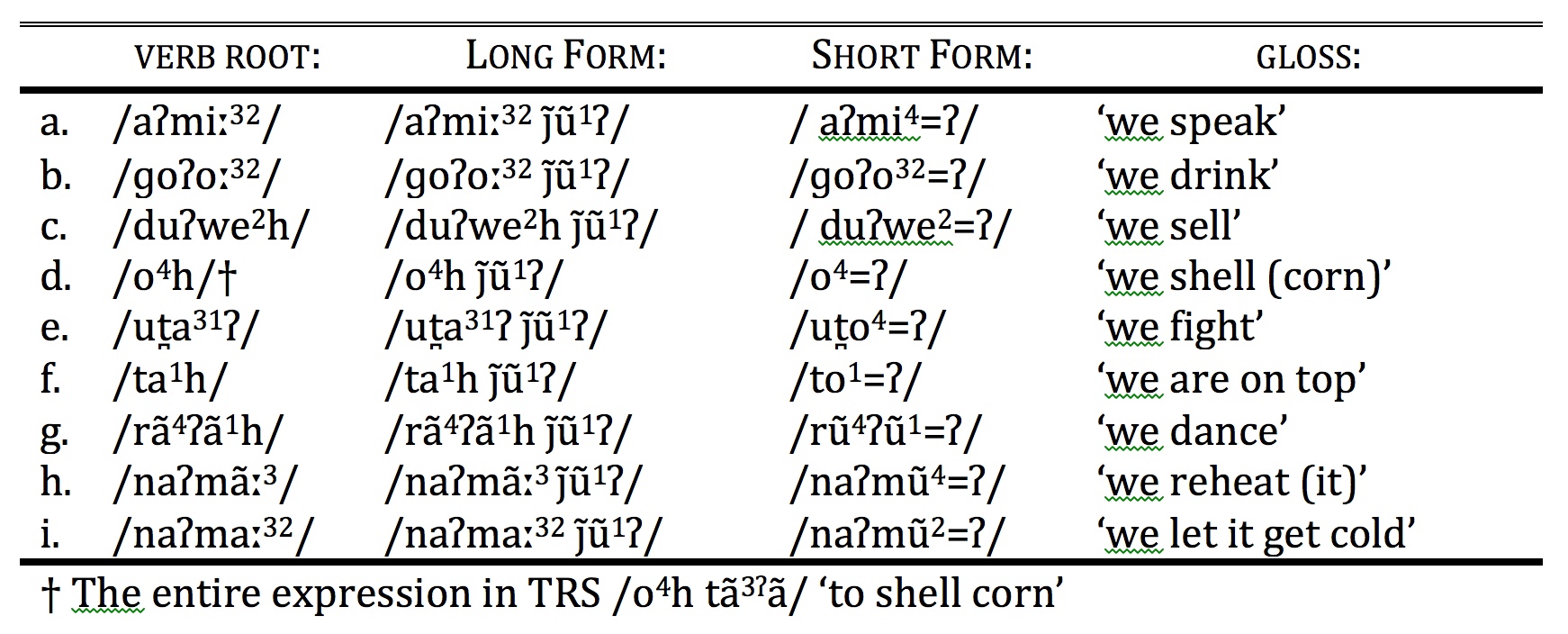

1INCL short forms are always marked with a glottal stop /=ʔ/ as illustrated in the examples in Table 12 below. There are some verbs that undergo tone raising in the formation of 1INCL short forms, for example, (a) /aʔmiː32/ ‘speak’ goes to /aʔmi4=ʔ/ ‘we speak’, while others maintain the tone of the root along with the addition of glottal stop as in (b) /ɡoʔoː32/ ‘drink’ and /ɡoʔo32=ʔ/ ‘we drink’. There are other verb roots ending in /h/ that undergo /h/ deletion and glottal stop replacement as a marker of 1INCL. For example, (c) /duʔwe2h/ ‘sell’ changes to /duʔwe2=ʔ/ ‘we sell’ and /o4h/ ‘shuck (corn)’ changes to /o4=ʔ/ ‘we shuck (corn)’. Verb roots that end in /a/ or /ã/ change to /o/ and /ũ/ respectively in the formation of 1INCL forms. For example, (e) /ut̪a31ʔ/ ‘fight’ changes to /ut̪o4=ʔ/ ‘we fight’ and (f.) /t̪a1h/ ‘be on top’ goes to /t̪o1=ʔ/ ‘we are on top’. If the root has a glottal stop /ʔ/ between two central nasalized vowels, for example /ãʔã/, both vowels change to /ũ/, as in (g.) /rã4ʔã1h/ ‘dance’ which changes to /rũ4ʔũ1=ʔ/ ‘we dance’. In TRS the vowel change moves regressively through a glottal stop when both vowels are nasal, but not through any other intervening consonant, for example, in (h.) /naʔmãː3/ ‘to reheat’ and (i.) /naʔmaː32/ ‘to let get cold’, only the final nasalized vowel changes to /ũ/ while the vowel before the glottal stop remains as is, for example, /naʔmũ4=ʔ/ ‘we reheat (it)’ and /naʔmũ2=ʔ/ ‘we let it get cold’.

TABLE 12: 1PL Long and Short Forms in TRS

FUTURE and PAST tense forms take an aspectual prefix [ɡa]-, [ɡi]- or [ɡV]- that distinguishes these forms from the present. Contrastive tones are generally found on the prefixed inflectional morphemes which indicate tense, usually tone /3/ for the past and /2/ for the future. Present and past forms end in the same tone or tone contour as the root (Good, 1979:107).

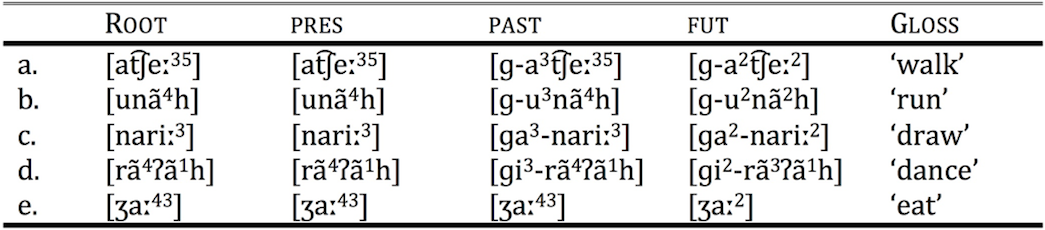

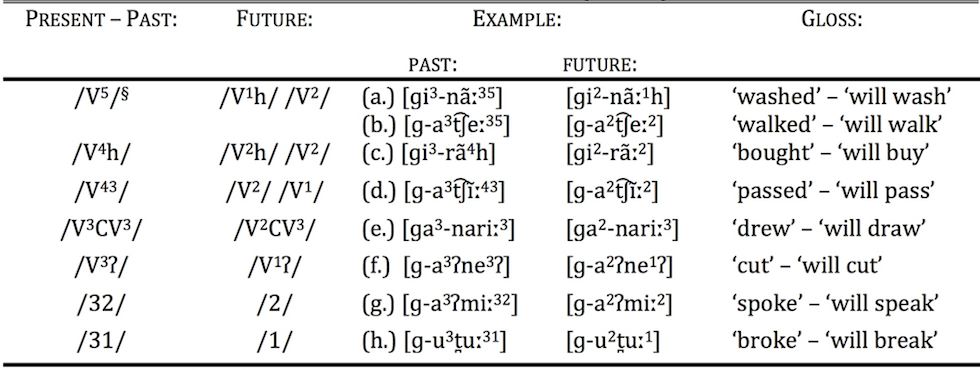

Table 13 illustrates aspectual prefixes used in the formation of the past and future tenses in TRS, along with the root in the formation of the PRESENT. Items (a.) and (b.) in the table below take the aspectual prefix /ɡ/- in the formation of the past and future tenses. For example, (a.) [at͡ʃeː35] ‘walk’ changes to [ɡ–a3t͡ʃeː35] ‘walked’ and [ɡ–a2t͡ʃeː2] ‘will walk’ and (b.) [unã4h] ‘run’ changes to [ɡ–u3nã4h] ‘ran’ and [ɡ–u2nã2h] ‘will run’. The TRS verb (c.) [nariː3] ‘draw’ takes the aspectual prefix /ɡa/– as in [ɡa3–nariː3] ‘drew’ and [ɡa2–nariː2] ‘will draw’. Item (d.) [rã4ʔã1h] ‘dance’ illustrates the use of the prefix /ɡi/– with forms such as [ɡi3–rã4ʔã1h] ‘danced’ and [ɡi2-rã2ʔã1h] ‘will dance’ in the formation of the past and future tenses, respectively. There exists a small subset of verbs, for example [ʒaː43] ‘eat’, cf., item (e.) below, in which the present and past tenses are indistinguishable and are context dependent. For example, /ʒaː43/ may be translated as ‘eats’ or ‘ate’ while the root undergoes tone lowering in the formation of the future, e.g., /ʒaː2/ ‘will eat’.

TABLE 13: Sample aspectual prefixes in TRS: present, past and future

Verb roots ending in a high tone not only acquire the aspectual prefix in tone /2/ in the formation of the future tense, there is also a concomitant lowering of tone in the final syllable. This finding lends credence to Mastukawa’s (2009:2) claim that high register tones undergo tone lowering in the final syllable in order to distinguish the potential aspect (i.e., future) from a completive aspect (i.e., past). For example, the TRS verb (b.) [a3t͡ʃeː35] ‘walk’ in Table 14 below, retains the tone of the root in the formation of the past tense, e.g., [ɡ–a3t͡ʃeː35] ‘walked’ but lowers to tone /2/ in the final syllable in the formation of the future, e.g., [ɡ–a2t͡ʃeː2] ‘will speak’. Other verb roots ending in a tones /53/ /43/ /4h/ /V3ʔ/ /32/ and /31/ lower the tone of the final syllable to tones /2/ or /1/ in the formation of the future; cf. items (a.) through (d.) below. Table 14 summarizes tone lowering patterns in the formation of the future tense in TRS as proposed by Matsukawa (2009:2). The examples provided in Table 14 were recorded by the consultant and author of the text and support Matsukawa’s reported findings. (For more information regarding TRS tone and aspect, see Matsukawa 2009). Although Matsukawa lists verb forms ending in level tone /5/, this tone is always realized as a glide in final syllables, for example: /35/ or /53/.

TABLE 14: Tone Lowering Patterns for the Future Tense in TRS (Matsukawa 2009:2)

While the text below contains no examples of the present there are several examples of past tense forms, for example: [ɡ–a3t̪a3h] ‘PST–say’, [ɡa3–nanɯː4] ‘PST–tell’ and [ɡa3–wĩː3] ‘PST–be’. There is also one future form included [ɡa2–na2wĩː3 ɡɯ̃2] ‘FUT–become warm’. There are also two examples of tenseless or unmarked verbs. The TRS word [nũː2] ‘be.in’ and [nita3h] ‘there.be.no’ are used in the present but are unmarked verb forms used to discuss on-going events in the past.

Sentence final particles.

In TRS and other Triqui languages as well, there are sentence-final particles used for questions, commands, affirmative and negative sentences. In TRS, not all sentences end in a final particle. Hollenbach (2008:141) reports that TRC may have as many as sixty sentence final particles. Hollenbach adds that the most common sentence particles in TRC are used in the formation of declarative, persuasive and negative statements, in addition to particles that signal questions, desires, or commands. The most commonly used sentence-final particles in TRS are: nanj anj /nã2hã3h/ used with affirmative declarative sentences, mânj /mã4h/, for negative declarative sentences, and rà’aj /ra1ʔa3h/ which is used for questions that require a response from the listener. Although the original written version of the text did not contain any sentence-final particles, the consultant appended nanj anj /nã2hã3h/ at the end of the legend. When queried, he indicated that it was to signal the end of the story and that it was the equivalent of a sentence-final period.

- While minimal pair contrasts can be found for glottally interrupted vowels that have a glottal stop, (i.e., /VʔTV/) and true vowel-glottal stop-vowel lexical items (i.e., /VʔVːT/), syllables that are interrupted by /h/, (i.e., /VhTV/) do not form minimal contrasts with /VhVːT/ words which do not exist in TRS. [back]

- TRS morphophology is very complex and cannot be fully presented in great detail in this paper. The purpose of this section is to provide the reader with an overview of the TRS verbal system. Consequently, it is not intended to be a comprehensive study of TRS verb morphophonology but rather it is designed to serve as a point of departure. For additional information on TRS verb conjugations, see Good (1979:105–107). [back]